Published in Newcity (April 2023)

Kushala Vora/Photo: Mark Blanchard

From the moment it begins, everything is an interaction. Kushala and clay. Kushala and wood. Kushala and lime, and fresco. Kushala and chalk and paint and brass. Kushala Vora’s studio showcases no fewer than a dozen projects, in as many mediums, all in stages of development. Sometimes, when she enters the studio, she holds her hands to her face like blinders, shielding herself from the art’s pleas to be worked on.

Most days she starts with something fast. “If I had a potter’s wheel, that would be where I’d head,” she says. “It’s like a hi, hello, how are you doing? It gets the focus going.” She points at a dozen or so flat-backed clay pieces on a big, central table. She calls them “sketches,” because they are quick to make. “There is always one process in the studio that I don’t have to think about, that I come in and I’m like, let’s just start with this,” she says. “That’s not to say I don’t enjoy it, there are moments that happen where I’m just like, ‘woooahhhh,’” she says, pointing at a bubble of folded clay covered in a melt of green and yellow glaze.

“Unearthed,” porcelain, terra cotta, fossilized notebooks, 2021

Those “woooahhhhs” guide a lot of Vora’s work. Her signature “woooow amazing” has so much breath behind it that it doesn’t matter what she’s talking about, I agree. It’s through keeping her hands moving—shaping, listening, trying, thinking, shaping, listening—that she discovers where the pieces want to go. “When you’re intensely working with the material, sometimes the material tells you things,” she says. The projects interact with each other in unexpected ways. Working on one thing might give her ideas, tricks or advice for another. She’s okay with setting something down for a while. And when she gets stuck, she thinks about Ernest Hemingway.

“Bodies Made by Habit,” tools by hand brass, river clay, sand, rust, 2019

“He has this quote in ‘A Moveable Feast,’” she tells me. “He says there’s a lot of agony when he’s trying to find something to write. So when that happens, he just peels an orange, and throws the peels in the fire, and watches them burn, and tells himself that he just has to find one thing that’s so true that he can’t deny it, and go from there.”

The truth carried by a Vora piece doesn’t only contain its final form, but its first home as well. For instance, a set of drawings that Vora created by layering scenes from an Indian school day on transparent paper use imagery that is too complicated to show in India without explanation. On the other hand, here in Chicago, their more potent cues—the hairstyles, the anklets, the choice of dress on her figures—might be missed. Until she can find the right time and place to show them, she’ll keep them in limbo. “I always get very amazed by people that are showing the same work in different places. I’m like, but how do you know what people are seeing?” she says.

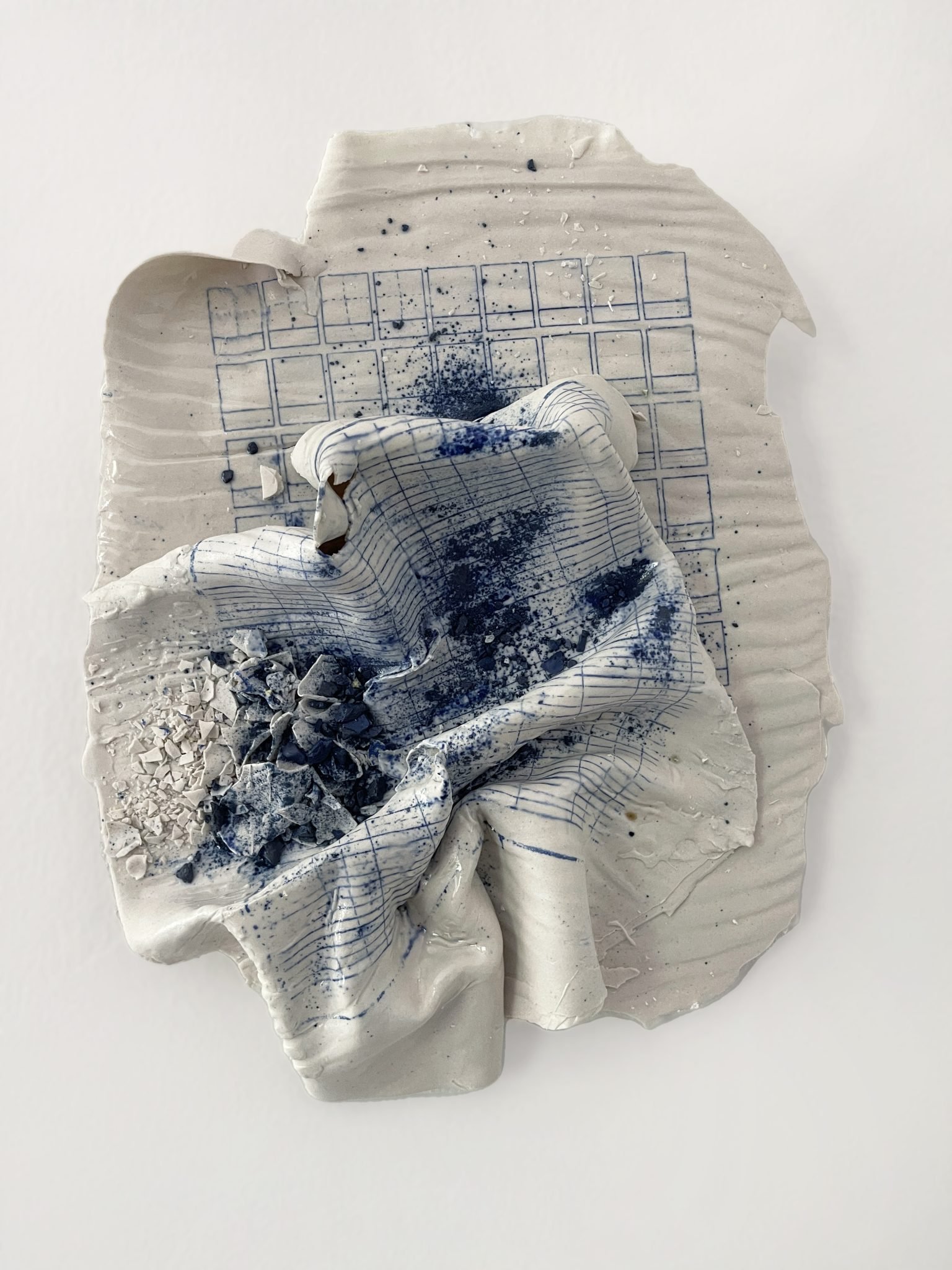

“Rule/Ruled,” porcelain, 2022

Vora was born and raised in Panchgani, a verdant rural village in India nestled into the Sahyadri mountains. She came to Chicago in 2016 to work on her MFA at the School of the Art Institute. When Vora graduated, she spent a lot of time with the question of place. What would it mean to stay in Chicago, she wondered. There was a lot she liked about the city, like access to people and their projects, but there were other details that were hard to square, like the light. “When I go home I see every sunrise and every sunset. Here, there were nights when I didn’t see the moon, days when I never saw the sun,” she says. “It’s different because I was grounded in that.”

During the pandemic, Vora spent ten months back in Panchgani. When she returned to Chicago, she felt at ease with being away. “I was able to go back and find some sort of home again, in a place that had kind of become somewhere I would just visit from time to time,” she says. “I was like, oh wow, things resonate, things still resonate, and I think I realized that wherever I go I will carry this place. So now it doesn’t affect me as much.”

Picturing Vora as unaffected is counter to how I’ve come to know her as an artist. She is the type of person who takes everything in, uncertain about where it will go or what it will mean, but confident that it is meaningful. This belief in the process grounds her work, while her omnivorous curiosity gives it levity. She is less cool, unaffected artist, and more inquisitive and trusting Hemingway, tossing pieces into the fire, fascinated by the flame and what truth will emerge.